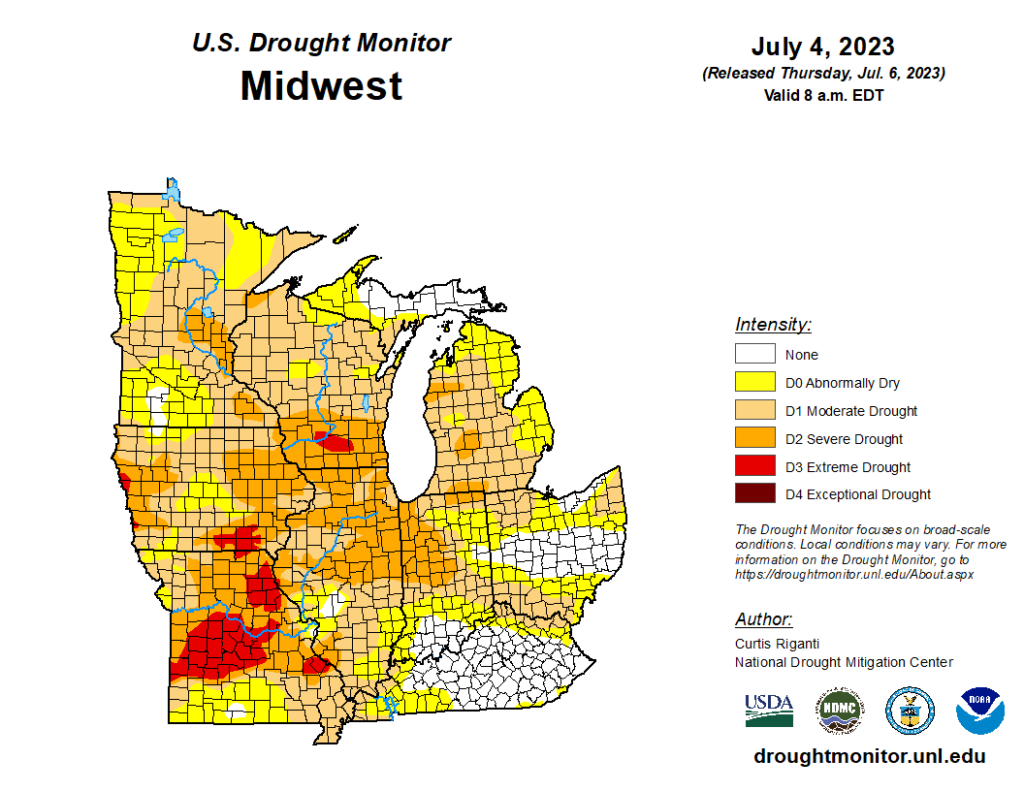

Sometime around the first week of June, it became clear that what was a half-mentionable stretch of dry weather to end May was quickly becoming more serious. Long-range weather models signaled drought, soils began to dry, and grain markets responded accordingly. In my career yet, I have not seen crop futures pivot so aggressively on each successive weather forecast as they did in mid-June. Acreage across Illinois grew increasingly desperate for rain and considering the national budget of corn and soybean production accounted for locally, this was enough to shake markets in Chicago. As the month ended, some areas in Illinois had experienced one of their driest June’s on record. Despite recent rains, nearly half the state remains in severe drought as of July 6th – although further improvement is likely.

Figure 1 USDA Drought Monitor (7/6/23)

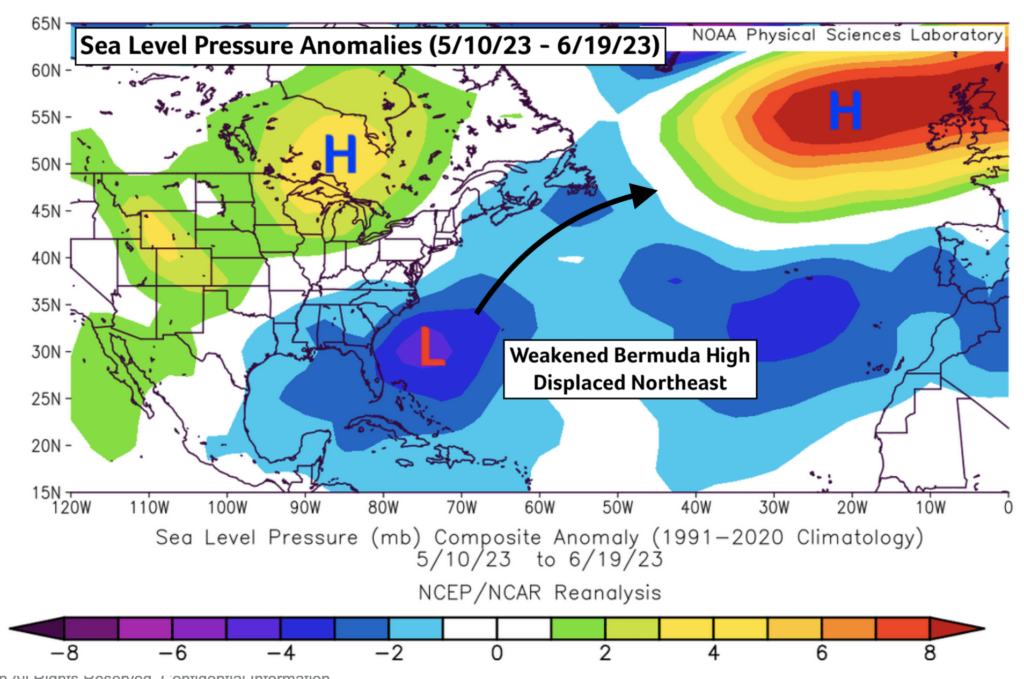

Earlier this year, there was hope that a developing El Niño would promote a wetter growing season in the Midwest. While the pattern seems to have shifted wetter here in July, it does warrant a debrief of the dry –and perhaps unexpected — pattern experienced this past June. For starters, the semi-permanent Bermuda High was especially weak in May and June. This area of high-pressure is typically situated off the East Coast of the U.S. near the island of Bermuda (which lends its name) and helps funnel rich Atlantic moisture into the Central U.S. With that feature essentially missing from the West Atlantic, we struggled to generate moisture return into the Midwest. Where we did observe anomalous high pressure was in eastern Canada where warm temperatures and dry conditions influenced the development of wildfires and their meandering smoke plumes which became an almost daily feature of the drought in Illinois near the end of June.

Figure 2 MSLP Anomaly Average (5/10 – 6/19)

Associated with the high-pressure in Canada was another important influence in the development of the drought: a weaker jet stream. That fast moving current of air aloft helps to organize and strengthen low-pressure systems which in turn help focus rain across the Central U.S. With a weaker jet stream, we saw fewer weather fronts, low-pressure systems, and thus chances for storms. The good news for crop fields across the Central U.S. is that the jet stream restrengthened and began to shift over the United States in just the last week or two. This has helped to return more frequent storm chances to Illinois. Unfortunately, this also meant the return of severe weather chances.

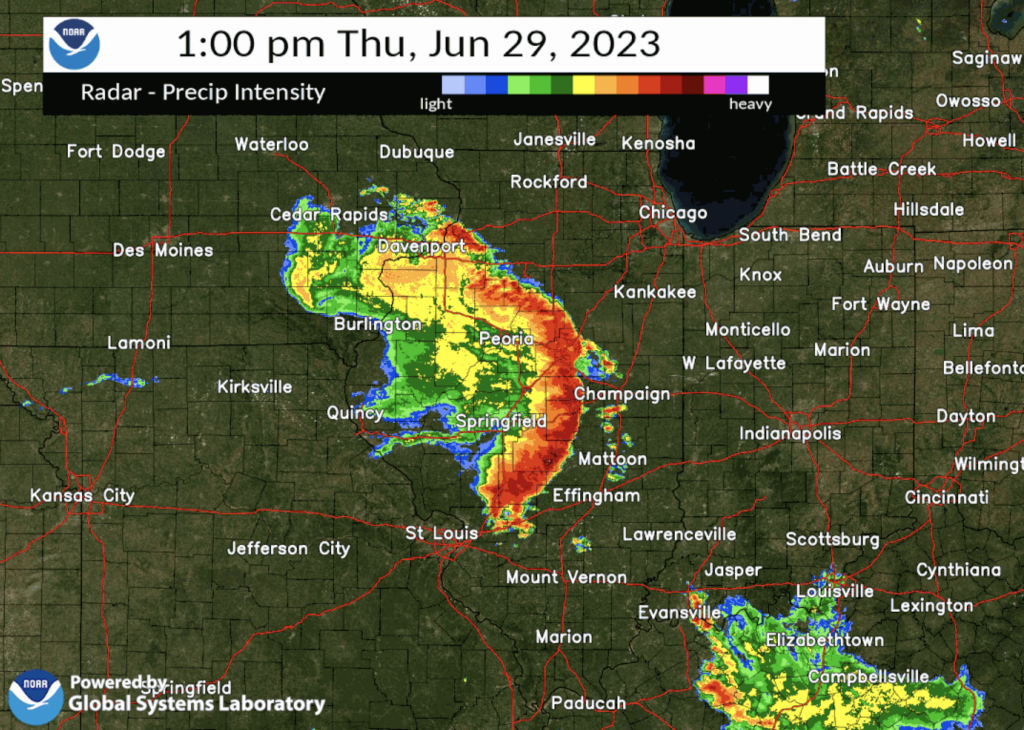

On the morning of June 29th, 2023, a growing complex of storms was observed moving east from the Missouri-Iowa state line. The storms gathered strength as they crossed the Mississippi then Illinois rivers. By mid-day, a wide swath of damaging straight line thunderstorm wind gusts (what meteorologists call a “Derecho”) was painting itself across the state. Power outages, brief tornadoes, tree and property damage were reported across many counties. At the time, it was hard to ignore that many of these same areas were receiving beneficial rainfall amid a severe drought. The event reminded me of an old saying in both agricultural and meteorological circles: big droughts end in big storms.

Figure 3 NWS Radar Image (6/29/23 Derecho)

The drought isn’t over in the Corn Belt, not yet at least. That said, significant rains and the return of that jet stream flow have eased fears of major water or heat stress impacting the crop during the critical reproductive growth stages ahead. In years past, we’ve seen soybeans specifically fend off significant drought well into July before responding to eventual rainfall in late July or early August. Should we continue this trend of periodic storm chances, we are likely on our way to a crop more on trend than we would have guessed in mid-June.

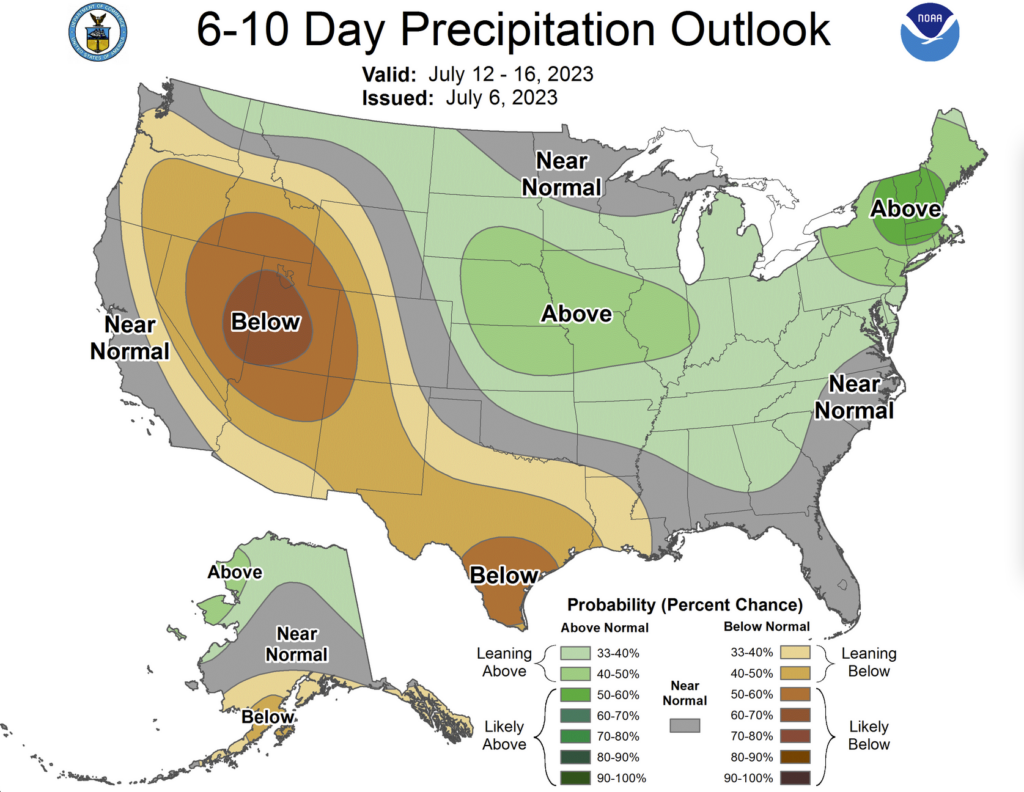

Looking ahead through July, the forecast remains friendly for crops in the near-term. Roaming thunderstorm complexes are forecast to continue across Illinois through at least mid-July. The ECMWF and GFS weather models have both forecast healthy rain totals across Illinois and the wider Soybean Belt over the next week or two. The Climate Prediction Center (CPC) has followed suit with a broad area of higher-than-normal precipitation chances extending through similar geography in their week two forecast products – taking us out through July 16th.

Beyond that, some conflicting signals have added uncertainty to the late July and August forecasts. There still exists some of the same features in global sea surface temperatures that likely played a role in the May – June Drought. Cooler ocean waters off the West Coast of the U.S., which can help promote ridging and dryness in the Central U.S., are still present. The anomalously warm waters in the Atlantic Ocean are persisting as well and those may have influenced the weaker Bermuda High which is still evident in near-term forecasts. That said, El Niño continues to strengthen in the Central Pacific, and the recent pattern shift toward more frequent precipitation chances is consistent with the typical El Niño-like pattern I expected to define this growing season. It’s for that reason I am not sounding any alarms on any sort of restrengthening drought in Midwest, but we’ll have to watch to see how the pattern evolves later this month.

Figure 4 CPC Precipitation Outlook (7/12 – 7/16)

El Niño autumns typically run wetter along the Mississippi River Valley and that would include Illinois and much of the Soybean Belt during harvest. The risk for shortened harvest and workability windows will be heightened this fall. It’s hard to look too far ahead in the forecast when we know these next few weeks here across the Midwest will be the most important in growing this year’s crop. Lastly, happy belated Fourth of July!

Matt

matt.reardon@nutrien.com

and then

and then