In the 20th century, observant fishermen off the coast of Peru noticed a pattern. When the often-cool Pacific Ocean waters in their bountiful fishing areas warmed, their catch shrank. Colder ocean water is nutrient dense within which organisms and fish thrive. With warmer temperatures, less fish made it into the nets and the industry struggled. Since these changing waters and the weather responsible for them surrounded the Christmas season, the Spanish speaking fishermen dubbed this phenomenon “El Niño” or “the child” signifying the Christ child. It’s unlikely these local fishermen could have imagined the tremendously impactful phenomenon they had stumbled upon. What we now know as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) drives significant changes to global weather patterns. We call the warm phase of this oscillation El Niño which is marked by warmer than average waters in the central and eastern Pacific. The cold phase of this oscillation is called La Niña – each cycle lasting between 3-7 years. A developing El Niño often begins to show itself as rapidly warming ocean temperatures in the far eastern Pacific, just off the coast of Peru.

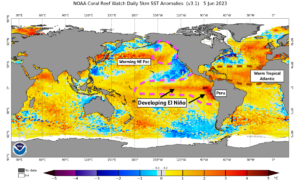

Figure 1: Sea-Surface Temperature Anomalies (6/5)

In the central United States, we often associate El Niño with friendly weather conditions for crop yields. El Niño summers tend to be wetter on average with less extreme summer temperatures. Water temperatures in the Equatorial Pacific are indeed warming quickly here in early summer. In fact, some of the fastest warming water has been observed just off the coast of Peru in the eastern Pacific – still home to a bustling fishing industry. Given this and modeled forecasts, it’s looking increasingly likely that we officially enter El Niño status in the Pacific in the coming weeks. The Climate Prediction Center (CPC) has issued an El Niño Watch with the probability of entering El Niño status around 90% this summer. While this is good news for growers in Illinois, ENSO is not the only weather influencing feature we must account for.

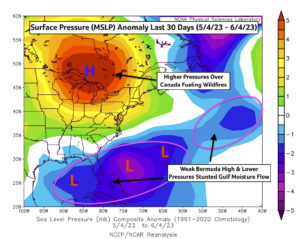

Despite the developments in the Pacific, conditions have remained dry across the Corn Belt. Persistent high pressure over Canada and lower pressures near the Gulf of Mexico helped to cut-off that valuable connection of moisture between the Atlantic and Illinois acreage. That tandem pressure pattern influenced historic wildfires in our northern neighbor which has billowed smoke and impacted air quality across the Eastern U.S. in early June. Those lower pressures in the Gulf of Mexico spurred the development of our first named tropical storm in the Atlantic, Arlene. The Bermuda High, a near-permanent atmospheric high-pressure system situated off the East Coast of the U.S. (near Bermuda), has been notably weaker over the last few weeks. Typically, the Bermuda High helps to funnel rich Atlantic moisture into the Corn Belt, yielding rain chances, during spring and summer. With that high pressure system weaker, we’ve seen less moisture flux from that rich moisture source to our south. Additionally, this influenced a relative lack of severe weather reports across the state in the last month.

Figure 2: Surface Pressure Anomalies (5/4 – 6/4)

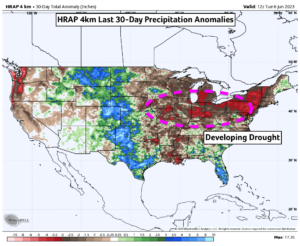

Drought has returned to Illinois as the lack of rainfall and periodic warmth worked to dry soils across the state. Spotty showers and storms brought temporary relief to some counties, but a growing portion of the state is now officially in drought status per the latest USDA Drought Monitor. Developing El Niño conditions in the Pacific should work to return moisture to the state as we move through the heart of summer. That said, dry soils have begun to stress a young crop across the state and mid-month rains, forecast as early as this weekend (June 11th), are of growing importance. Confidence has increased in recent days for healthy rain chances both this weekend and later next week (~June 15th – 17th). Beyond that, there is considerable model spread between late June forecasts. Still, it’s looking more likely than not that we return to warmer conditions with more seasonal precipitation chances to close this month – that will be a worthwhile exchange if we can get the water.

Figure 3: Last 30 Days of Precip Anomalies (5/6 – 6/6)

The latest ECMWF (European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts) seasonal forecast for this summer shifted drier for Illinois. This was a marked change to what was otherwise a consistent forecast for a wetter than average summer for the Corn Belt. I have reasons to think this drier forecast has a misleading bias in that direction due to recent soil deficits (which the model initializes with) and a drier short-term forecast (which the model can place more significance on). Warming ocean temperatures in the Central Pacific (El Niño) and recent warming in the Northeast Pacific (PDO) both correlate with wetter summer months in Illinois. These correlations aren’t absolute, however, and warmer ocean temperatures in the Tropical Atlantic may be offsetting the wetter influences in the Pacific at this time. I think it’s likely that the developing El Niño, which could be quite strong, will win this summer battle of influence and July will end wetter than average across most of the state. Recent dryness, now reflected in soil moistures, and competing influences in the Atlantic will work to keep some drought risk and uncertainty in the mid-summer forecast, particularly for areas that miss out on the upcoming mid-June rainfall.

Figure 4: Latest ECMWF Summer Precip Anomaly Forecast

Should conditions turn wetter in July, a large share of that rainfall will be convective in nature i.e., thunderstorms. Some of these El Niño summer thunderstorm complexes can be quite strong, and we may be tracking Illinois severe weather again in the coming weeks. While we commonly think of April and May as our peak severe weather seasons in the Midwest, July and August see their share of severe weather as well. Given mature crop stands later in the summer, these storms can be more impactful to agriculture. Some of the more recent strong tornadoes in Illinois history occurred in July (Roanoke F4, 2004) and August (Plainfield F5, 1990). That’s not to say we’re scheduled for another powerful tornado this year but simply to remind ourselves the severe weather season isn’t over yet despite the recent hiatus.

and then

and then