Nitrogen is a key ingredient in soybean production, how does it help the plant. As a legume, Bradyrhizobium bacteria infect a root of a soybean plant and the plant builds nodules to house them. A community of rhizobia in the nodule grab nitrogen (N) from the soil and “fix it” into a form that a plant can use. The plant in turn feeds the microbes—this is not in dispute. However, the amount of nitrogen fixed is estimated to be enough for 50-bushel soybeans, with the rest coming from the soil. With the pursuit of 80, 90 or 100 bushels, growers feel the need to add supplemental nitrogen, but yield responses are inconsistent.

Ignacio Ciampitti, soybean specialist at Kansas State University, presented an online webinar through the American Society of Agronomy blog titled New Insights into Soybean Biological Nitrogen Fixation on Aug. 30. He said that from 1920 to 2016, yield increased 360% while biomass increased 410% and that yields today are directly associated with the size of the plant and amount of foliage produced. He also said, after looking at data from 1980 to 2013, that increases in yield are primary due to increases in seed number per acre and not seed weight.

Ciampitti said that increases in biomass have led to increases in nitrogen demand. “Soybean demand for N increases with yield. Beans require 100 lbs. nitrogen/A for each 20 bushels or 5 lbs. nitrogen/bu. With this information we are estimating total nitrogen demand, yet we have failed to understand the underlying relationship.”

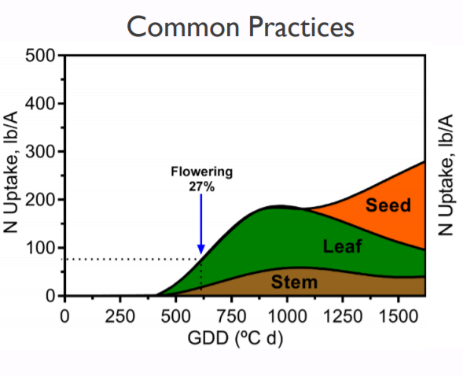

Soybeans take up N, either from nodules or the soil. Ciampitti pointed out that only about 25 percent of the N uptake occurs before flowering during a period of low demand and with the foliage being the primary repository of that N early. The image to the right shows the N uptake pattern for a 51 bu/A soybean crop that was grown with little intensification, requiring only 300 lbs. N. In contrast, an 80 bu/A crop requires 500 lbs. N, yet only takes up 100 lbs. by flowering, just 20% of the total.

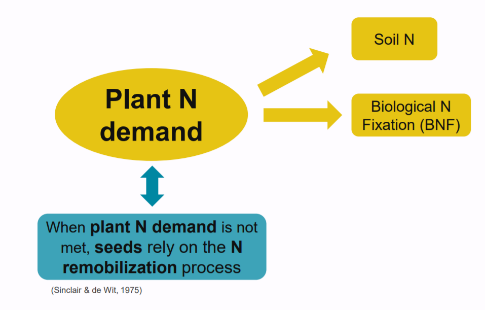

The preferred source of N is from biological nitrogen fixation (BNF). BNF increases from early in the growing season (June) through flowering pod fill. It generally peaks out during seed fill and then declines. “BNF satisfies N demand until 200 lbs. N/A (40 to 50 bushels). As yields increase the N-gap increases. As demand for plant N increases the soil will have to provide more N to meet yield expectations,” explained Ciampitti.

He explained that BNF can be low, moderate or high in a plant depending on soil conditions, health of the plant and presence of a viable rhizobia population in the soil. The lower the BNF, the greater the N-gap and the more the crop will depend on soil N. “Only under very low N fixation levels (<44%), the BNF strongly relates to final soybean yield. Thus, a superior yield increases the N deficit and the need for soil N to satisfy soybean N demand,” said Ciampitti.

He explained that BNF can be low, moderate or high in a plant depending on soil conditions, health of the plant and presence of a viable rhizobia population in the soil. The lower the BNF, the greater the N-gap and the more the crop will depend on soil N. “Only under very low N fixation levels (<44%), the BNF strongly relates to final soybean yield. Thus, a superior yield increases the N deficit and the need for soil N to satisfy soybean N demand,” said Ciampitti.

Until we can estimate BNF in the field to predict the N-Gap in the crop and mineralizable N from the soil, we won’t be able to develop a strategy for recommending N on beans, including when to apply and how much.

To learn more view “Soybeans and Biological Nitrogen Fixation: A review. Ignacio Ciampitti and Fernando Salvagiotti in Better Crops http://www.ipni.net/publication/bettercrops.nsf/article/BC10235/.

Soybean agronomist Daniel Davidson, Ph.D., posts blogs on agronomy-related topics. Feel free to contact him at djdavidson@agwrite.com or ring him at 402-649-5919.

and then

and then