by Stephanie Porter and Stephanie Smith

Why is there such interest in sulfur (S) now and why is it important for our yields? Sulfur deposits have changed dramatically over the years due in part to air quality improvement efforts. Owners of coal-fired power plants have invested more in scrubbers, decreasing the amount of acid rain we receive.

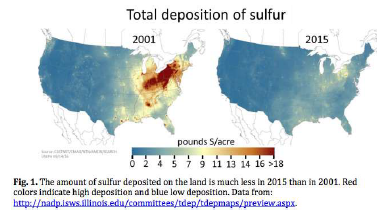

Acid rain brought atmospheric sulfur to our soil, and now sulfur deficiencies are more common in some areas that used to receive more acid rains. The map below shows the decrease in the amount of sulfur deposited. Areas in and around Indiana went from almost 15-20 lbs. of sulfur in 2001 to almost 0 lbs. in 2015.

Sulfur helps plants utilize other essential nutrients much more efficiently. In addition to boron and potassium, sulfur is key in nitrogen uptake and use in plants. Sulfur deficiencies can be identified early in the growing season by flashes of interveinal yellowing. We typically see these deficiencies when the plant is handing off uptake from the seminal root system (seed) to the nodal root system (plant).

nutrients much more efficiently. In addition to boron and potassium, sulfur is key in nitrogen uptake and use in plants. Sulfur deficiencies can be identified early in the growing season by flashes of interveinal yellowing. We typically see these deficiencies when the plant is handing off uptake from the seminal root system (seed) to the nodal root system (plant).

While plants can grow through deficiency symptoms, it doesn’t necessarily mean the yield-robbing effects are over.

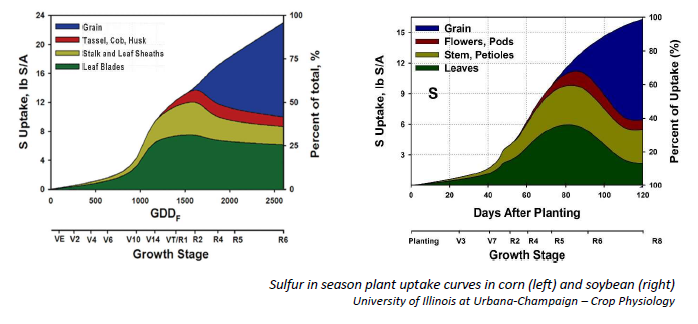

The graphs above show corn and soybean sulfur usage. A corn plant takes 52% of its sulfur needs post-tassel. A soybean plant takes up 85% of its season sulfur needs during reproductive stages. These late-season needs, during grain and pod fill, mean you should consider sulfur application, especially if sulfur deficiency symptoms appear mid to late in the growing season.

Both corn and soybeans can benefit from sulfur application and yield advantages have been seen in many recent trials across many states. Traditional soil testing is a good place to start, but it does not predict sulfur deficiency. However, it can track changes in soil sulfur levels over time. Another is a tissue test, comparing plants with deficiency symptoms to those that appear healthy in the same field at key growth growth stages, can indicate if plants are sulfur deficient.

Sulfur application will depend on soil type and tilth, yield goals and adequate soil pH (6 – 6.8). For each percent organic matter, you can expect about 3 to 4 lbs. of sulfur could become available for your next crop. Corn grain removes about 0.5 lbs. of sulfur for every 10 bushels of grain harvested and soybean grain removes about 1.7 lbs. pounds of sulfur for every 10 bushels of grain harvested.

There are many ways to apply sulfur and the type you apply will depend upon availability and profitability. The nutrient is as mobile in the soil as nitrogen so soil drainage, for example, in a sandy soil may require a higher application rate or a multi-application per year approach. A good range of full-season application rates for corn and soybeans should be 15 to 30 lbs./A sulfur.

A popular source of sulfur appears to be ammonium thiosulfate (ATS), which is applied with UAN for corn or a preplant herbicide before corn or soybeans, but check tank-mixing compatibility and follow label restrictions.

On the other hand, some may recommend 500 to 1000 lbs./A of gypsum blended with other fertilizers every 3 to 4 years in poorly drained soils if Mg is not low. Other sulfur options are ammonium sulfate (AMS) which can be blended with urea for corn as well as potassium magnesium sulfate (sul-po-mag or K-mag) or potassium sulfate blended with potash, which can provide S and K for corn or soybeans.

If elemental sulfur is applied, it should be applied in the fall and in conjunction with another available sulfur fertilizer in the spring, because it must be oxidized by soil bacteria during warm temperatures with adequate moisture before becoming plant available.

Many growers worry that elemental S, ATS and ammonium sulfate will lower soil pH; however, if these are used to provide less than 30 pounds of sulfur per acre, the amount of acidity generated is equivalent to less than 100 pounds of limestone per acre.

For more information, check out https://www.agry.purdue.edu/ext/corn/news/timeless/sulfurdeficiency.pdf

and then

and then