Risk on, or risk off? That’s the question I’ve heard most from growers and industry folks over the past month. Whether it’s state summits or national conferences, people want to know whether the weather this year will bring undue stress, and I’m not talking about southern rust or variable tassel wrap reports. I mean the big stuff: region-wide flooding rains or prolonged drought. With markets and prices still forcing us to think harder about what this next growing season will bring, it’s just as important to assess where we’re at, or more importantly, where we’re not.

Starting Conditions: La Niña Fades, but Drought Lingers

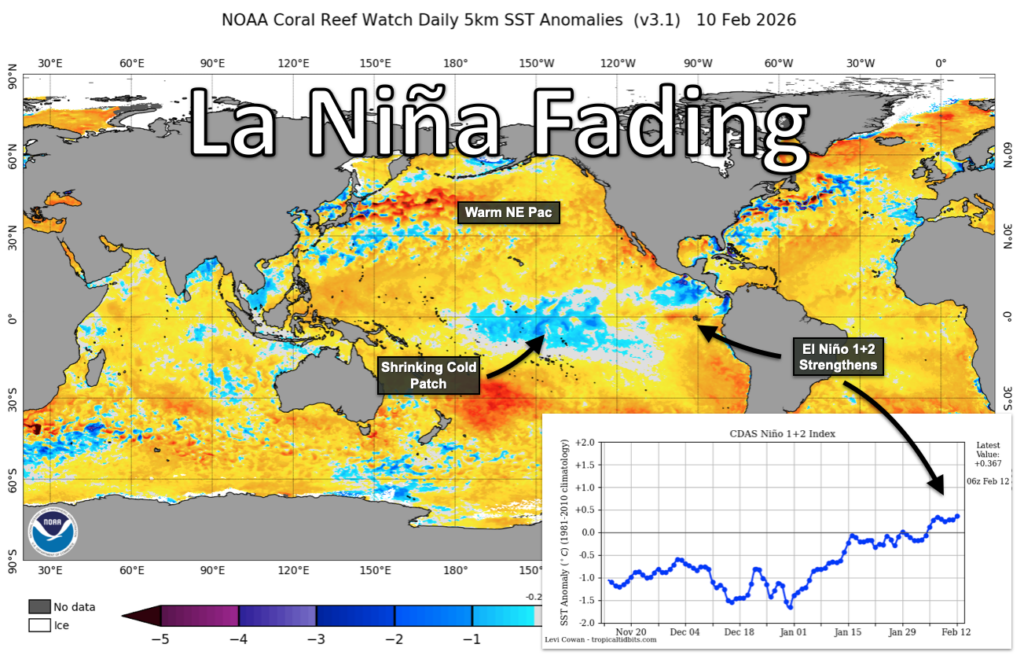

Where are we? We’re coming out of a weak La Niña in the Pacific. Cool water temperatures are fading in the tropical regions, fading quickly even, as sea surface temperatures begin to resemble more favorable analog years like 2018, 2014, and 2009. That’s only to say we’re starting out with better signs for moisture. But things can change.

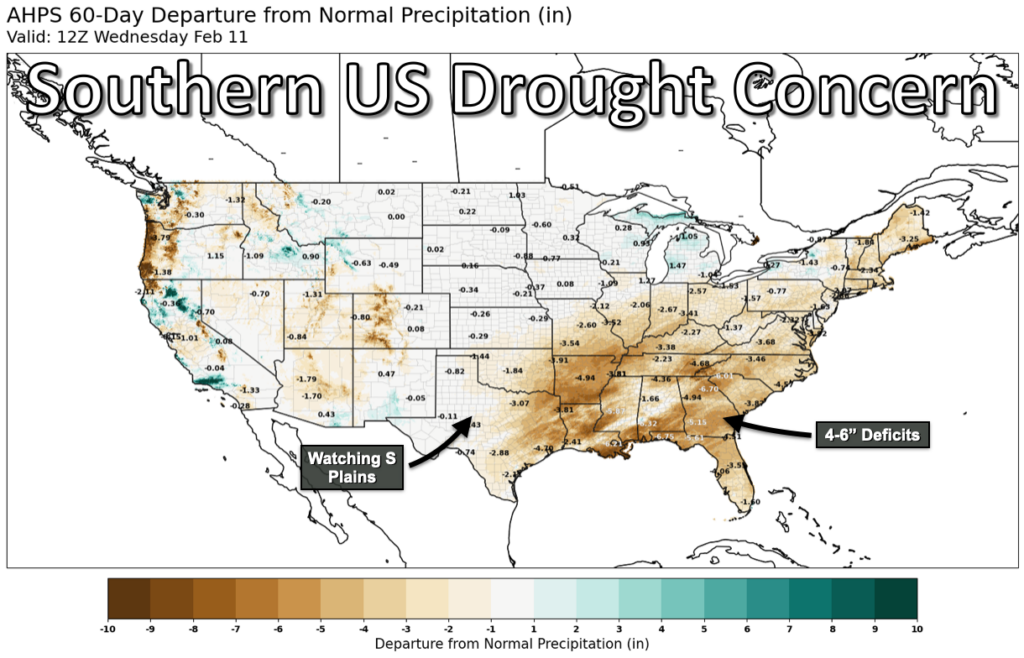

Despite the encouraging Pacific signal, we’re also staring down overwintered drought. This weak La Niña itself was a “double dip,” a repeat of the La Niña episode from the winter of ’24/’25. Repeat episodes of autumn drought, combined with frozen soils, have allowed soil moisture deficits to pile up across the region. This is the first spring I can remember in my professional career where folks around here have been hauling water. I know growers who didn’t haul in 2012. Let that sink in.

Is that a concern? It is. In forecasting, sometimes the most important factor is where you begin, not where you think you might be headed. We call that “persistence” in the forecasting field, and it’s a reminder to count your chickens early in the season. Don’t assume a wet spring is coming just because the Pacific looks friendlier.

A Brutal Winter by the Numbers

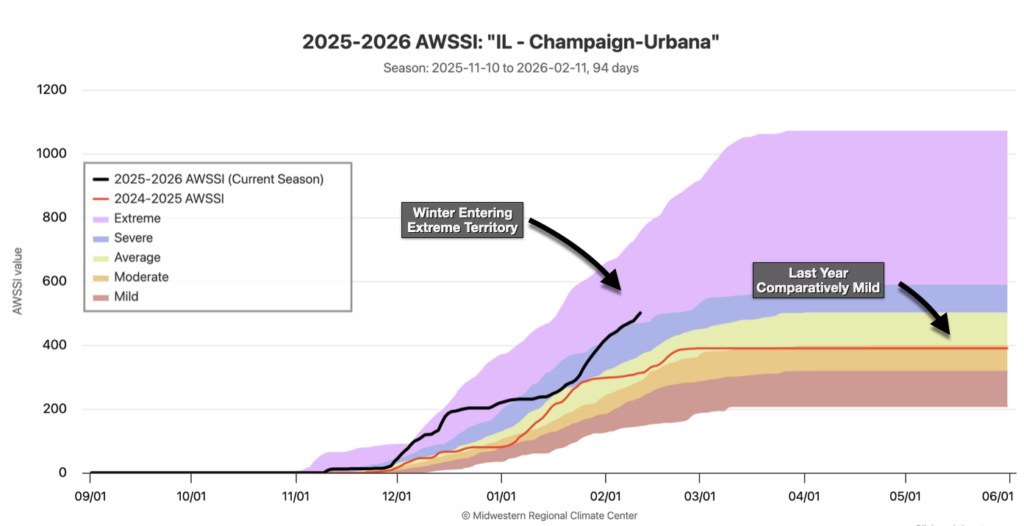

This winter also brought multiple spells of brutally cold temperatures, especially early on, along with heavy snowfall events for both downstate counties and the Chicago metro area. Many Central and Eastern Illinois cities are experiencing their harshest winter in decades.

One objective measure of winter severity is the Accumulated Winter Season Severity Index, or AWSSI. Developed to quantify and describe the relative severity of a winter season, AWSSI accounts for the intensity and persistence of cold weather, total snowfall, and the duration of snow cover on the ground. By any measure, this winter has earned its reputation.

Despite the harsh conditions, we’re climbing out of the cold of late January and increasingly seeing warmer days with improved rainfall potential. The Central U.S. could see two low-pressure systems next week, yielding multiple rainfall chances across the state. Spring, or even late winter, can quickly make up for overwintered drought.

The long-range forecast looks increasingly wet for the Midwest through the end of the month, with no sign of winter’s return. Yet.

A weakening stratospheric polar vortex (think of it as a spinning donut of air high above the North Pole) portends potential cold air outbreaks, perhaps by the end of the month or early March. It only takes living in this state a spring or two to learn not to say goodbye to winter too early. We’re usually in for at least one big chill, and often snow, well into March.

The Northeast Pacific: A Sleeper Signal Worth Watching

Something I’ll be watching closely in March and April is ocean temperatures in the Northeast Pacific. For all the talk of drought concern in the spring of 2025, driven by widespread overwintered drought and poor soil moisture across the Central U.S., those ocean temperatures stayed warm and even intensified into early summer. The result? Record precipitation across parts of Iowa and large yields despite southern rust pressures and eastern Corn Belt heat.

Here’s the mechanism. When the Northeast Pacific sees warm sea surface temperatures through spring, it tends to promote ridging across the western U.S., which in turn allows jet stream level flow, particularly the storm-friendly northwest flow regime, to dominate across the Corn Belt. It’s a reliable mechanism for staving off midsummer drought concern, even if it raises the risk for severe weather and derechos like we saw last summer. I’ll take the rain and the risk of wind over drought any day, and I think most growers would agree.

Where I’m Most Concerned: The Southern U.S.

If there’s one area I’m watching more carefully, it’s the southern U.S., particularly the southern Plains and the Southeast. Both regions have seen relatively poor winter precipitation despite bouts of cold air and scattered rainfall events. Drought south of Illinois has a tendency to spread north later in the year, so my eyes often turn to Little Rock or Nashville during spring as bellwethers for what might be coming.

Another area I’m keeping my eye on is the Western Plains, namely the Dakotas, Montana, and even Nebraska. A persistent lack of snow this winter has left them in what we call a snow drought. Poor late winter snowpack tends to correlate with increased drought pressure in spring and occasionally summer in those same states. As I mentioned, spring can make up a lot of ground, just as it did last year. But the starting position matters, and right now, the South and Plains are dry. Lastly, the Western U.S., particularly the mountainous regions, are running below their typical wintertime snowpack. While that’s critically important for water systems, river networks, and irrigation there, it also has a negative correlation with Central U.S. severe storm activity. While their snowpack is expected to improve next week thanks to this February’s pattern flip, the broader snowpack deficit there heading into spring might mean a comparatively less active season compared to what we encountered last year. What is certain is that in just a few weeks, we’ll be flipping our clocks forward an hour in early March. Regardless of any lingering cold air potential, that means sunsets will push near 7 p.m. instead of 5 p.m., and that’s going to make spring planting and summer warmth feel that much closer. The days are getting longer, the Pacific is warming, and we’ve got our eyes on the sky. Time to get to work.

and then

and then