Illinois producers have already navigated a dramatic start to the growing season, and the atmosphere looks primed for a summer light show of storms next week. May's weather offered a vivid illustration of just how different conditions can be between the northern and southern halves of the state, and those contrasts could shape yields as we move into the warmest weeks of summer.

The most memorable day so far was May 16, when a far-reaching outbreak of severe storms swept the central United States. Southern Illinois witnessed a long-track EF-4 tornado that carved a path near Marion, while earlier that afternoon a deadly tornado struck the St. Louis metro area. Farther north, high winds emanating from severe thunderstorms south of I-72 lofted dry topsoil and created an intense dust storm across central and northern counties. Chicago's visibility dipped below a quarter mile—low enough for the National Weather Service office in Romeoville to issue only the second Dust Storm Warning in the office's history. Those twin hazards showcase the larger spring pattern: southern counties remained soaked and storm-prone, while northern counties suffered from persistent, drying winds and a stubborn moisture deficit that still has portions of the I-80 corridor flirting with drought status via the USDA Drought Monitor.

An EF3 tornado near Sikeston, MO on 5/16/25 – Matt Reardon

In early June, Tropical Storm Alvin spun up in the East Pacific. Although storms like Alvin rarely reach U.S. soil, they still play a role in our weather. A typical East Pacific tropical system lifts enormous amounts of warm, saturated air into the upper atmosphere; as that latent heat is released, it tugs on the jet stream and helps shift summertime ridges. The end result can be a plume of tropical moisture that eventually arcs into the Southern Plains or even the Corn Belt. In Alvin's wake, Hurricane Barbara and Tropical Storm Cosme have already been named, and a fourth candidate, Dalila, appears to be taking shape. For growers, the takeaway is not so much about direct landfall as it is about timing: when the Pacific stays active, the odds rise for tug-of-war repositioning of the high-pressure dome that ultimately governs mid-summer heat.

Closer to home, many Illinoisans have wondered when summer will finally arrive. With daytime highs mired in the 70s and low 80s through most of May and early June, growing-degree-day accumulation has lagged the long-term average. That chill is particularly problematic in those northern fields that are also short on moisture; cool soils slow root expansion, nutrient uptake, and early canopy closure. On the positive side, studies consistently show that early-season setbacks can be erased if July turns cooperative. Corn, for example, can make up a surprising amount of lost GDD in just a couple of hot, sunny weeks before tasseling, provided that soil profiles are recharged first.

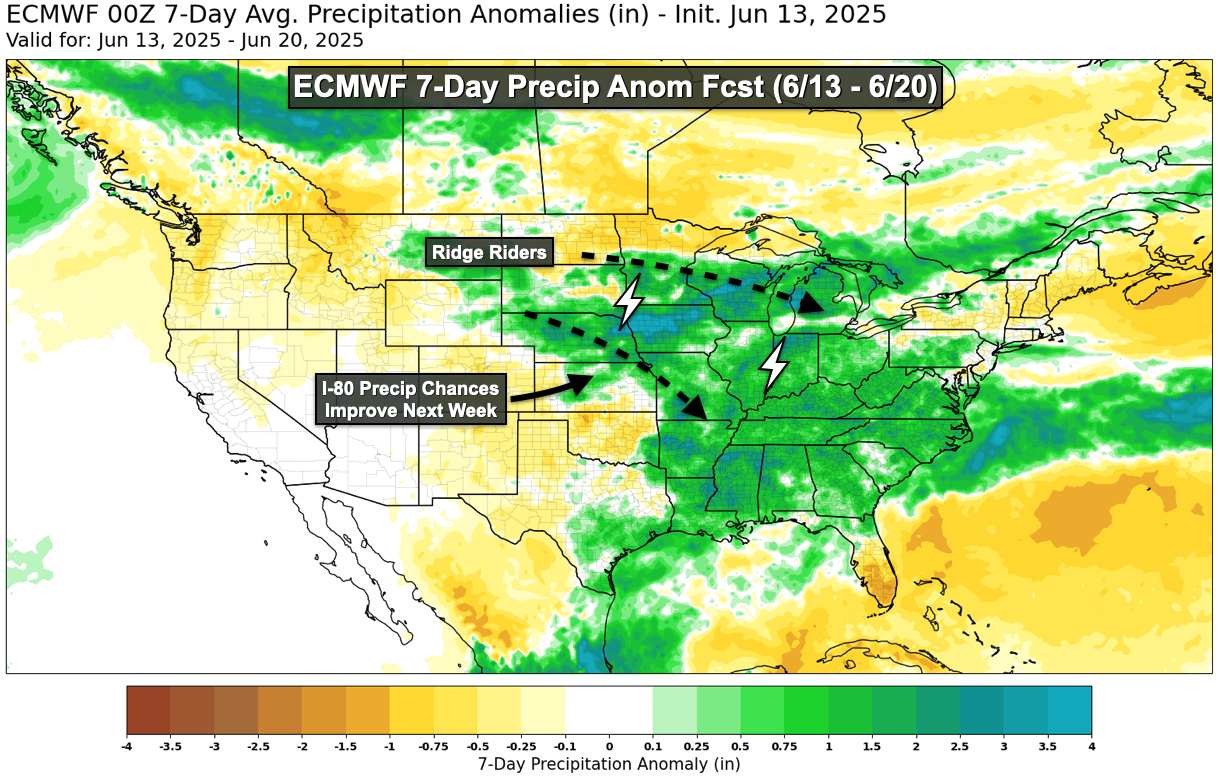

The week of June 9 finally finally delivered a taste of true summer, with upper-80 °F afternoons nudging GDD totals upward again. A weak low-pressure system will skirt the state this weekend, giving some central and southern counties a chance for a half-inch of rain or more. Next week's guidance then builds a stout upper-level ridge over the Central United States. That setup normally steers "ridge-rider" thunderstorm complexes from the High Plains into the western Corn Belt and often across Illinois. These mesoscale convective systems can be double-edged swords—one inch of rain and a shot of cool outflow may come bundled with damaging straight-line winds—but they remain a critical part of our summer water budget.

Elsewhere across the central United States, spring rains in the Mid-South recharged the very soil that later supplies evaporative moisture transported on southerly winds. That recharge has trimmed back regional drought risk. Even so, a wedge of acreage from Omaha to Chicago still shows pockets of soil moisture below normal, so the next ten to fourteen days will matter. If the anticipated storms deliver and 90-degree heat follows, young corn and soybeans will respond quickly, shooting upward into the long June sunlight. Interestingly, this moisture-sensitive corridor overlaps the historic Prairie Peninsula—a tongue of tallgrass prairie that once extended from the Great Plains deep into Illinois. Paleo-ecological studies suggest the extension was maintained not only by summertime swings in precipitation but also by frequent, low-intensity fires intentionally set by Indigenous peoples. In other words, the same stretch of ground that now hinges on timely June–July rainfall has long been shaped by a partnership between climate variability and human-managed fire.

The summer solstice arrives on Friday, June 20, at 9:40 p.m. CDT. At that moment the Northern Hemisphere reaches its maximum 23.4-degree tilt toward the sun. The change carries several agronomic implications. From June 21 onward, nights begin to lengthen—an important trigger for photoperiod-sensitive crops like soybeans, which initiate flowering once night length crosses a threshold. The weeks immediately after the solstice also tend to "lock in" the prevailing jet-stream pattern that will dominate through mid-July. Long range weather forecasts like the ECMWF point to a modest but manageable risk of midsummer drought: if June storms replenish topsoil now, the crop will have the resilience to ride out a brief hot spell in early July. For growers making management decisions, the message is one of cautious optimism.

In short, Illinois crops have started 2025 with both advantages and headwinds. Early coolness and dryness are undeniably hurdles, but the window for recovery is wide open if well-timed storms arrive over the next two weeks. May's dramatic weather reminded us how fast conditions can change; June and early July will decide whether those changes tilt toward record yields or renewed stress. Lastly, stay weather-aware. Ridge-riders develop quickly and are often poorly modeled by near-term forecasts. Have a way to receive weather warnings overnight by keeping your phone charged, weather radio on, or both.

Matt Reardon – Senior Atmospheric Scientist at Nutrient Ag Solutions.

and then

and then