In recent years, regenerative agriculture has been all the buzz. While the concept is not new, awareness of enhanced soil biology is more prevalent now than ever. So, how do you achieve soil that’s not only deep and rich in color, but also draws down carbon and is resilient in the face of numerous issues? There’s no single solution, but healthy soil practices can rebuild organic matter and restore degraded soil biodiversity.

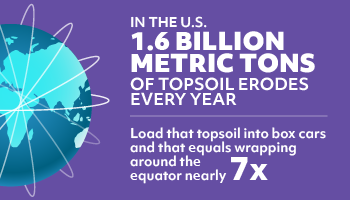

Currently in the U.S., 1.6 billion metric tons of topsoil erodes every year, according to Dr. Kris Nichols, soil microbiologist, KRIS Systems Education & Consultation. If that topsoil were loaded into box cars, the train would wrap around the equator up to seven times. That’s 174,307 miles of topsoil lost in a single year. While no-till is often the first practice to prevent erosion and protect the integrity of soil biology, it’s merely the tip of the iceberg.

Currently in the U.S., 1.6 billion metric tons of topsoil erodes every year, according to Dr. Kris Nichols, soil microbiologist, KRIS Systems Education & Consultation. If that topsoil were loaded into box cars, the train would wrap around the equator up to seven times. That’s 174,307 miles of topsoil lost in a single year. While no-till is often the first practice to prevent erosion and protect the integrity of soil biology, it’s merely the tip of the iceberg.

Just as tilling disturbs the natural state of soil, so do synthetic inputs of nitrogen or phosphorus. Although used with good intentions to improve nutrient availability, reducing synthetic inputs is crucial to improve nutrient use efficiency of plants.

“Plants use only 30 to 50 percent of applied nitrogen fertilizer because the fertilizer typically isn’t in a form continuously available to plants,” says Dr. Kris Nichols, Soil Microbiologist at KRIS Systems Education & Consultation. “It’s similar to dumping a week’s worth of fish food into an aquarium and expecting it to feed the fish for the entire week. The fish doesn’t know to regulate their food intake and what’s left over at the end of the week will likely degrade. The same is true with synthetic fertilizer.”

Plants live in an environment where they have everything they need to grow, but the proper nutrients aren’t always available for use. Lucky enough, biological activity supplies around 75 percent of plant-available nitrogen and 65 percent of phosphorus, delivering key nutrients crops need to thrive. And just like we need to eat throughout the day, soil needs year-round feeding as well.

By maximizing the amount of time carbon is put in the ground—a.k.a. days plants are in the ground—we can bring soil back to life, making it more resilient and productive. In Illinois, plants should be in the ground anywhere from 260 to 290 days to properly feed soil. However, that still leaves up to 105 days with no way for soil to receive carbon and other important nutrients. That’s where crop diversity comes into play.

“Integrating other plants through cover crops, companion crops or polycropping intensifies soil health systems,” says Dr. Nichols. “Not only will these additional crops help reduce soil erosion, they also provide much needed nutrients for soil and plants.”

Take wheat for example. When wheat is used as a double crop for soybeans, the two crops share nutrients. Mycorrhizal fungi play an important part of the relationship between wheat and soybeans as the fungi aid in transfer of nitrogen, carbon and phosphorus from one plant to another.

Mycorrhizal fungi can provide up to 90 percent of the nutrients plants need and also help obtain micronutrients including copper, zinc and boron. They create an interactive carbon economy to trade resources and improve nutrient and water movement, water infiltration and water holding capacity.

“Beyond sharing nutrients, companion crops also offer the benefit of added plant stress,” says Dr. Nichols. “Stress usually isn’t thought of as a benefit to plants. But plants actually produce many of the nutrients we look for in food, including antioxidants and polyphenols, while they are under stress.”

Competition from other plants or grazing by animals provides pressure needed to stimulate production of biomolecules that protect and improve plant integrity and create nutrients needed in human diets.

It’s safe to say that your soil biology has the potential to influence the future of your farm and drastically improve crop production. Every piece of land is different and soil biology decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis to enhance productivity and nutritive quality of your crops.

and then

and then