Last week I drove from Champaign to Peoria for a conference and got a clear look at the heart of Central Illinois in the middle of yet another fall drought. Dry crop stands, busy combines, grain trucks, and the occasional distant smoke plume stretching across an otherwise blue sky marked the drive.

Illinois has now experienced some level of moderate to severe drought in nearly every year of this decade, with the possible exception of 2021, when dryness was limited to the northernmost counties. This year ranks among the worst, with much of Central and Southern Illinois currently in severe drought. Rapidly drying crops and occasional field fires are a common sight across the landscape, though the lack of strong winds has helped limit what would otherwise be a serious fire danger.

That’s a contrast from this past spring, which was one of the windiest on record for the Midwest. Lately, we’ve seen few low-pressure systems or fast-moving fronts capable of bringing either wind or rain. If we had, we’d likely also have seen more thunderstorms and downpours—the kind of weather that’s been conspicuously absent. I can count on one hand how many rumbles of thunder I’ve heard this autumn.

Warmer-than-usual temperatures have made matters worse. Many counties in the state are tracking among their top ten warmest autumns on record, with frequent highs in the 80s°F and even a few 90°F days stretching into October.

The Missing Ingredient: Momentum

Since August, the atmosphere has been missing one simple but crucial ingredient for storm development: momentum. Meteorologists track west-to-east momentum across the globe to gauge how active or “progressive” the jet stream is. Those values have been below average since late summer, which has helped drought spread not only across Illinois but also throughout the Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys. The Mississippi River at Memphis now sits roughly six feet below low stage, approaching the concerning lows reached last fall.

Change on the Horizon

One silver lining to the lack of rain has been the absence of severe weather in recent weeks. Fewer thunderstorms mean fewer damaging wind and hail events—a welcome break after an active start to the year.

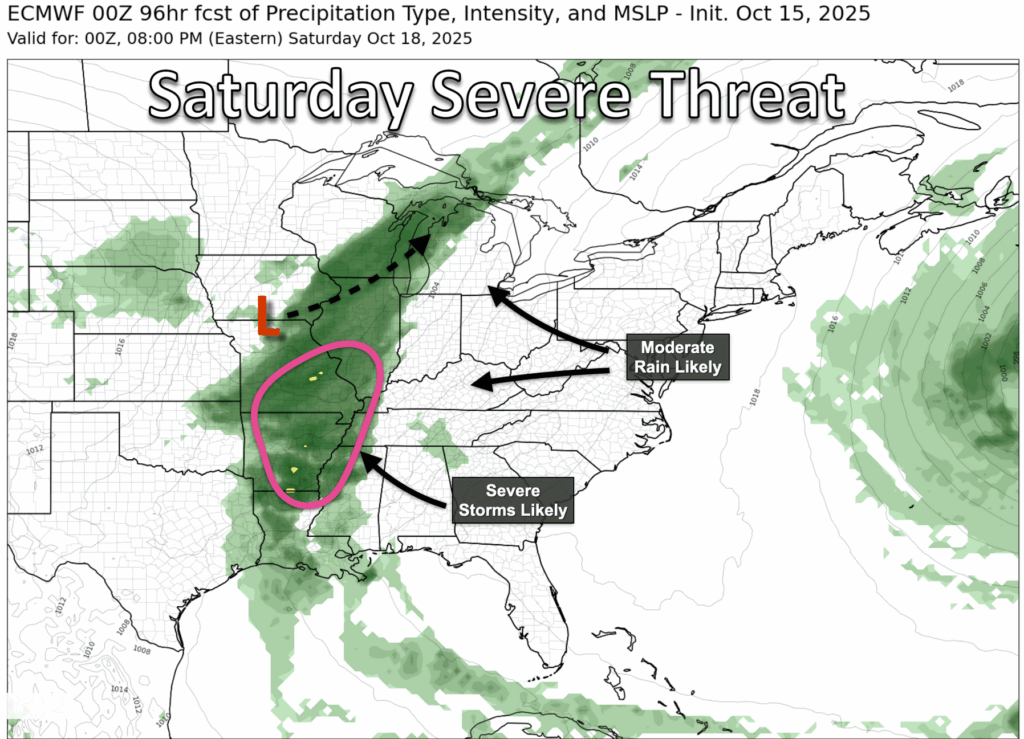

That may change this weekend. Atmospheric momentum is finally trending upward, signaling a more active jet stream across the U.S. This should help energize a series of stronger low-pressure systems and cold fronts, possibly accompanied by severe thunderstorms.

The first of these systems arrives this weekend, with the Storm Prediction Center highlighting an area of concern from southern Illinois down into Arkansas. Most of the Midwest, including Illinois, should see a widespread soaking, with rainfall totals of at least half an inch and some areas likely picking up an inch or more.

Cooler air will follow behind the cold front, but early indications suggest that while temperatures will return to more typical mid-October levels, widespread frost is unlikely just yet. The median fall freeze date in Illinois ranges from around October 18 in the north to as late as November 1 along the southern tip of the state. If recent weeks are any guide, this fall may see a later-than-usual first freeze across much of the region. Even so, a reinvigorated jet stream increases the odds of colder Canadian air masses dipping into the Midwest later this month, which could finally bring the season’s first widespread killing freeze.

The Global Connection

What’s driving this renewed jet stream activity? The answer begins half a world away in East Asia. An unusually strong high-pressure system is forecast to dive south out of Siberia—an area known for its massive “mega highs”—and into China and East Asia. As it presses against the Tibetan Plateau, this pressure configuration slightly resists Earth’s rotation.

To balance that resistance and conserve angular momentum, the jet stream speeds up in what meteorologists call a “mountain torque” event. This interplay between Earth’s rotation and powerful pressure systems bracketing the world’s tallest mountains helps kick the jet stream back into gear, returning us to a more typical fall pattern of cold fronts, gusty winds, and chilly rain. It may be what’s needed to bring drought relief to the state.

A Double Dip La Niña and a Quiet Atlantic

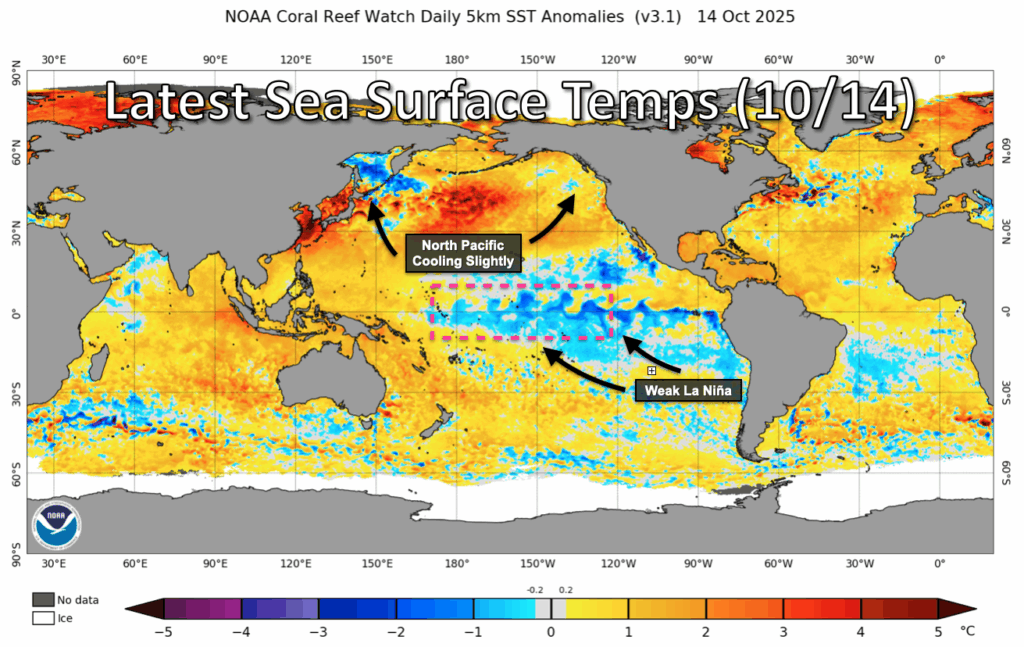

Last week, the Climate Prediction Center officially declared the onset of another La Niña in the Pacific—our second in as many years, sometimes called a “double dip” La Niña. Historically, La Niña winters in the Midwest tend to be more variable, with larger temperature swings and more frequent precipitation as the jet stream meanders.

This year’s event is expected to be relatively weak and peak early, with models already hinting at a possible transition toward El Niño conditions by mid-2026. While such long-range forecasts are far from certain, an eventual El Niño would bode well for next year’s growing season, since those patterns typically reduce drought risk across the Corn Belt.

There’s also some good news from the Atlantic. It’s been a relatively quiet hurricane season, with few storms forming in the Gulf of Mexico or the Caribbean. That means fewer threats to the U.S. mainland. Aside from a couple of close calls with Imelda and Erin, most storms this year have curved harmlessly out to sea, including newly named Tropical Storm Lorenzo, which poses virtually no risk of landfall.

Long-range models suggest a tropical wave in the Atlantic could drift into the southern Caribbean Sea late next week, where it might organize further. Should that occur—and if the system remains intact in the often-unfavorable southern Caribbean environment—it will be worth revisiting near the end of the month for even a remote chance of U.S. landfall.

Looking Ahead

As the growing season winds down in October and November, my travel schedule predictably picks up again. With several trips planned across the Midwest this fall and winter, I’m curious to see what the view out the window will bring—whether it’s more stretches of dry, barren fields or rain-soaked ground soon covered by fresh snow. That simple difference will say a lot about how this drought story evolves as we head into the new year and the next growing season.

Matt Reardon

matt.reardon@nutrien.com

and then

and then