Like many across the country, I awoke on the morning of Friday, July 4th, eager to celebrate with friends and family. For those of us tracking the latest weather, excitement gave way first to concern, then to sorrow, as news emerged of the catastrophic flash floods that struck the Texas Hill Country.

In the early hours of July 4th, a mesoscale convective complex—essentially an organized cluster of intense thunderstorms—formed about 100 miles west of Austin, TX. As the complex decayed, it left behind a mesoscale convective vortex, a rotating cluster of storms with tropical storm-like traits. These slow-moving thunderstorms dropped staggering rainfall amounts, likely well exceeding 10 inches in just a few hours, equivalent to several months’ worth of precipitation. This unfolded over a region already prone to flash flooding due to its steep terrain, thin soils, and narrow watersheds. A wall of water then surged more than 25 feet in just 45 minutes, overwhelming campsites and low-water crossings.

As of July 10, this event has tragically claimed more than 100 lives, with dozens still unaccounted for. This disaster will rank among the deadliest flooding events in U.S. history. Meteorologically, the ingredients were in place, and the outcome was tragic. A rich tropical airmass left behind by Tropical Storm Barry provided elevated precipitable water values, a measure of moisture in the lower atmosphere, while weak upper-level steering winds allowed the thunderstorm complex to linger. Hill Country topography, known for its thin, hard soils and “flashy” rivers—streams that rise and fall quickly—did the rest.

The scale of the disaster is already sparking debate about warning dissemination, forecast office staffing, and even the role of cloud seeding — though not implicated in this event. These conversations matter, but they belong in after-action reports once search teams stand down. For now, our thoughts remain with the families and first responders.

Zooming out, the past 30 days have been wetter than average across large portions of Iowa, Nebraska, and Minnesota, wiping out many lingering spring deficits. Illinois hasn’t been as lucky. Storms have often “died on the vine” crossing the Mississippi, leaving pockets of moderate drought along and north of the I-80/I-39 corridor, with some fields already showing leaf-curl—a clear sign of water stress in corn. Acres across North Central Illinois, Northern Indiana, and Southwestern Michigan are reporting drier-than-average soils and a few signs of crop stress. In fact, Illinois was one of the few states showing a downward trend in corn conditions during this recent stretch.

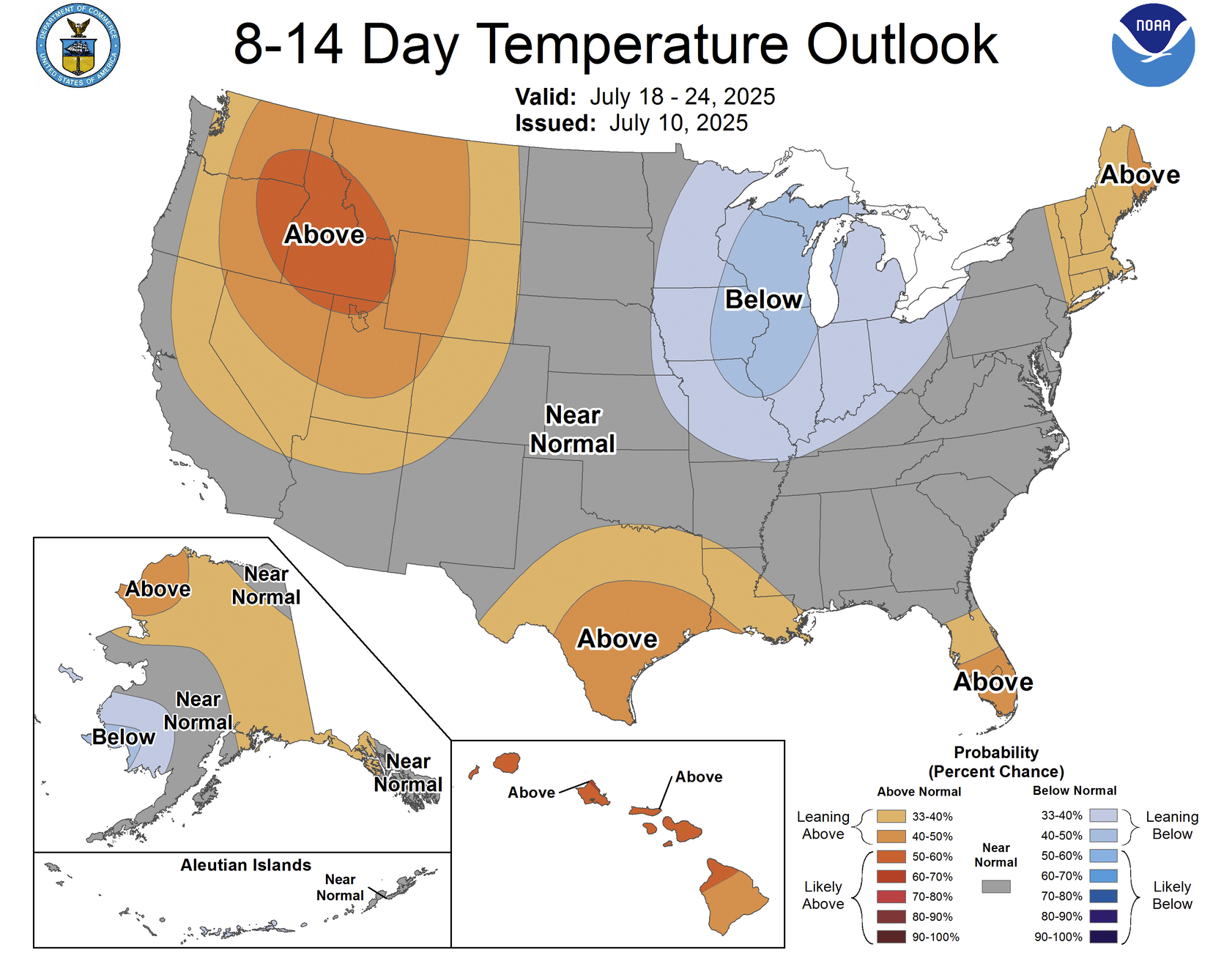

Additional rain chances this week will be especially beneficial as corn crops are rapidly tasseling across the state. The synoptic setup looks favorable. A persistent ridge over the Northwest U.S. and Western Canada is channeling northwest flow into the Midwest. This summer conveyor belt often spins up thunderstorm complexes on the Plains and sweeps them east overnight. These systems can soak one county and skip the next, but they also cap daytime highs and help keep overnight lows in check.

Why fuss over nighttime temperatures? Research shows that sustained nights warmer than about 72°F during the reproductive phase of corn growth reduce both kernel number and weight, ultimately trimming yield. Current guidance points to a few muggy nights but does not suggest a persistent heat dome through mid-July. That’s good news for both corn and soybeans. The absence of intense mid-July heat is often just as strongly tied to yield potential as timely rainfall during these crucial weeks.

This shift toward a more favorable July forecast is partly due to recent warming of sea-surface temperatures in the Northeast Pacific. Historically, even modest warm anomalies in that quadrant correlate with cooler, storm-friendly Midwestern summers. Markets have clearly taken notice. Typhoon activity in the West Pacific has energized the North Pacific Jet Stream and helped usher warmer waters from the North Central Pacific toward the North American coastline. Our best corn and soybean yielding years tend to occur when that region of the Pacific warms in July, and that pattern appears to be taking shape again in 2025.

It’s easy to forget now, but just a month ago, crop stands looked underwhelming. A cool start to June, lagging GDDs, too much moisture in southern counties, and too little in northern areas left the door open for later-season stress. Well-timed rain and heat in late June have rapidly corrected those early growing season issues. Driving around the state, I see stands that look full of potential, reminding me of some of our best yielding years, despite a few problem areas mentioned above.

In just a few short weeks, we’ll turn the calendar to August and approach the climatological peak of Atlantic hurricane season. This week, Colorado State University released its reputable seasonal forecast, calling for a slightly above-average season with 16 named storms expected. A “named storm” refers to any tropical cyclone that reaches tropical storm strength or higher. Moderating this higher-end forecast are recent pockets of cooler sea-surface temperatures in the Atlantic’s main development region—an area where many early-season storms first organize after emerging from African easterly waves. Hurricanes need warm water and low wind shear to intensify. Given recent episodes of upper-level shear across that region, it’s reasonable to question whether the basin will ultimately reach the higher end of forecast activity. If not, that would be a welcome development, especially after last year’s above-average season, which included the devastating impacts of Hurricane Helene. Still, as I remind folks every summer: it only takes one landfalling storm to define a season. Hurricane Andrew in 1992 remains the textbook example, it was the first named storm in what was otherwise a quiet season by storm count.

Closer to home, the year is far from over, and a proper heat episode will almost certainly return before August wraps up. But if just-in-time rains continue, Illinois is likely on track for a record crop. The latest USDA/NASS crop conditions illustrate widespread yield potential, with the best July corn ratings in recent memory. Soybeans are trailing their 2024 year-to-date condition ratings and, as always, are especially sensitive to August weather. Still, there’s meaningful upside, particularly with mid-July shaping up to be as low-stress as the current forecast suggests.

As we enter the heart of summer, attention will be split between the tropics and the fields. In these two arenas, the weather still holds the power to rewrite the story of the season. For now, cautious optimism feels justified on both fronts.

Matt Reardon

matt.reardon@nutrien.com

and then

and then